One important thing I learnt from 18 years of education in China, is the importance of “free will”.

Now, I for one, do not believe in the absolute concept of it, i.e. being completely free in the way we think. After all, there are a sufficient number of credible scholars who’d be eager to point out the number of uncontrollable factors that build our brains, impact how we interact with the world and influence our decision making process intimately – e.g. the languages we speak, the families we grow up with, the cultural and religious landscapes we come from etc.

What I did learn though, from both reflecting on my own journey and observing those around me as fellow competitive hardcore Chinese nerds, is that – while a wide range of external motivations could drive us along, only our sense of agency would sustain our fuel for decades. And the start of this journey dates back to my teenage years.

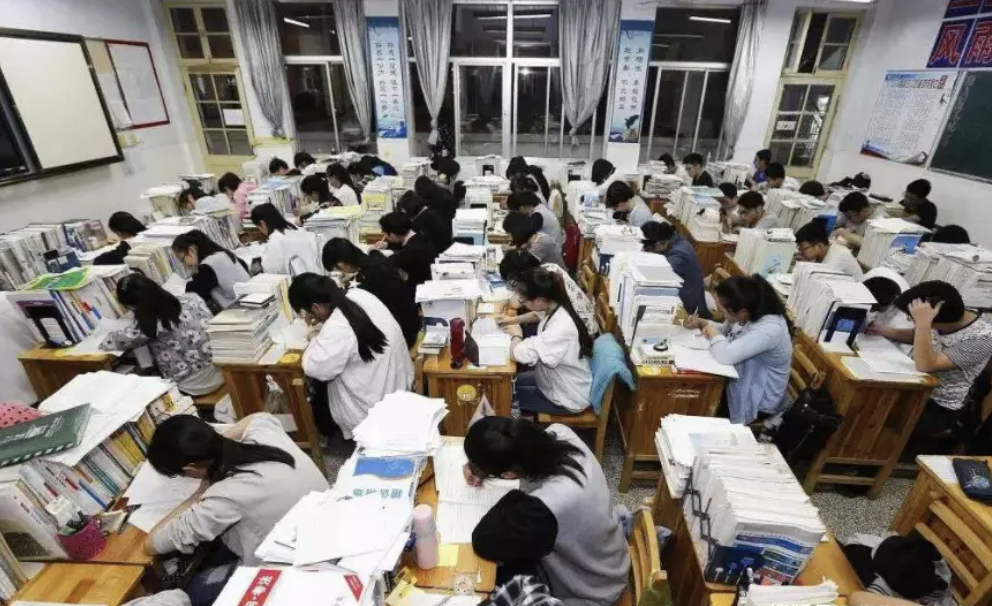

For those who might not be familiar with the Chinese secondary education system in the 90-20s (it might still largely be the same at its core but this is an important disclaimer that the system may have well evolved since), it was heavily dependent on scoring high in all exams across six subjects. As a science track student, I spent 12-14 hours a day and 6-7 days a week on Physics, Biology and Chemistry on top of the mandatory subjects of Maths, English and Chinese Literature. University entrance qualification was entirely dependent on the precise total score ranking amongst all contestants in the same year (i.e. ~300K students in my province in my year). All these is to say, it was a tightly governed learning environment for anyone, let alone teenagers with wild imaginations and hormones.

Our ambition then was very singular and clear – to score high. Why?

- scores were constantly in display, i.e. a total score ranking of all students based on monthly mock exams would be published on a blackboard in the campus

- classes would be reshuffled based on the ranking, i.e. you could move from #1 class of 60 students with the best teachers to #2 or lower-ranked classes if scored sufficiently lower in the most recent monthly exam

- by reshuffling classes, it meant physically packing books and moving across to a different classroom where everyone knew why you moved here, and still bumping into classmates you hanged out with in prior months who also knew why you moved out

The fear of public shaming was so effective at motivating all of us to suppress our innate desire to play, to mate or to chill around as teenagers, and dedicate hours and hours drilling to rank high and move up the classes. After all, most of our self-worth and social currencies were entirely constructed by the scores and rankings we achieved each month. It was my first intimate experience with the power of external motivations.

I’ve learnt that it could be incredibly effective at getting immediate results, e.g. score high enough in the next monthly exam to stay in the #1 ranked class; and yet it could also be so fragile that it could hardly sustain us for a longer time horizon, e.g. it was not uncommon to see those with high scores became completely lost after entered some of the best institutions in the country. Because just as the force of external motivations could be so strong that it would drive one through years of drilling, its absence could be capable of creating a black hole with gravitational pull weighing us down just as strong, if not more.

Sitting where I am today, I’ve also learnt to appreciate that it’s almost impossible to avoid driven by any external motivations completely. And they would typically fall under a few broad categories:

- As a teenager, it could come in the form of a fear of public shaming, or a fear of disappointing parents;

- As a functioning adult, it could evolve to a fear of failure, a fear of poverty, a fear of social disapproval or losing status, or a craving for validation from those with perceived power etc.

On the contrary, our sense of agency comes in all shapes of forms. What underpins it all is the clarity in what we want and where we are headed. It recognises that our choices and efforts affect the outcomes we experience, despite of what’s outside of our immediate control. It puts us in our driver seats. Instead of being driven by external motivations, we choose to drive on the path we take, and we are more than just a passenger on the back seats.

As I navigated through this intense pre-college schooling years, it became clearer to me at some point in my mid-teens that I wanted to explore the world, and more specifically, “to live in and explore as many countries and cultures as I possibly can”. Sitting where I am today, having gone through pages of my own handwritten journals, it remains unclear how it came to be. Where was that even coming from? I’ve questioned myself often.

- It could have come from the very first English movie I saw? It was Titanic so would’ve been even more bizarre because it should have sufficiently planted the fear of transatlantic travels in my underdeveloped brain.

- It could have come from Kobe Bryant’s childhood and multilingual upbringings? He was my first role model outside of parents and grandparents.

- It could have come from my obsession with outer space and science fictions?

- …

The list could go on but almost two decades later, I am still not entirely sure where that voice in my head first originated. What I am grateful though is that I (and equally important, my parents) allowed it to manifest, however unrealistic it might have sounded at the time, and let it run its course. It had since helped me prioritise and make decisions that may have seemed senseless to some at the time, but ultimately guided me to precisely where I am today.

As I leaned in over time, at some point –

- it became my reason to sit through soul-numbing chemistry classes, because I learnt I needed to score sufficiently high in all subjects to maximise the chance of going to Hong Kong;

- it helped me decide between a perceived higher ranked institution in Beijing and a mid-tier university in Hong Kong, because I learnt that latter would afford me a stepping stone into the globe;

- it ignited my passion for English, because I appreciated that I needed it to communicate well and support a multi-cultural lifestyle.

It could be so simple, because all I did was being in-tune with that soft voice in my head early on and let it grow to become my driving force for decades to come. Yet it could also be so hard, because the voices from external motivations could be much louder if we let them.

- Sitting through the chemistry classes was not my choice, and it could have been because I feared scoring poorly and moving classes and being laughed at, or because it played a non-negotiable role in enabling my scholarship to Hong Kong.

- Going to a famous institution in Beijing would have won me higher social status then than going to a mid-tier university in Hong Kong; and that status could have been more important than exploring a new culture.

- Learning English via an original routine – practising famous public speeches out loud in English, alone, in an open football field, during lunch time under the hot sun in Southern China – won me a reputation of being a lunatic at school; it would’ve been tempting to give it up had I not really wanted to learn how to speak English well.

In retrospect, the clarity we need to support our sense of agency could be ever fluid – it may not come to us at an early age, and it can change over time. And not all of them would make sense to us early on. But that’s okay. For instance, I have now learnt to recognise that more countries don’t equate richer experience or expanded personal growth necessarily. And the latter overtook as a bigger driving force.

That appreciation, however, is informed by calibrated reflections based on a sufficiently extensive set of real-life signals. It helped me to appreciate that being an active participant in shaping our own journey regardless of what’s outside of our immediate control, is an acquired experience.

It’d require us to pay close attention to what could be some of the smallest voices in our heads, and allow them to take their course.

It taught me that there are sufficient externalities as it is that are eager to take control of our agencies if we let them.

It showed me that it’d be an infinite journey to listen to, to be the best champion of our aspirations and to stay committed to what we truly want.

And eventually, our sense of agency will take us where we are meant to be.

(As always, feedbacks are adored)